How war made the first cities

Early cities as fortified structures —did Neolithic conflict drive urbanization?

The walls of Bronze Age Jericho

Why do cities exist?

For about 300,000 years, humans lived in nomadic groups of a few dozen people. Families made small, temporary shelters— thatched huts covered with grass, or perhaps animal hides or sod in colder climates. We moved camp every few months, following the flush of plants, the migrations of animals, sources of water. As we did, we abandoned old camps and houses, and built new ones.

Around 10,000 years ago, that started changing. We invented new ways of getting food- farming grains, herding animals, fishing. As a result, we started making larger, more permanent settlements, in places like Jericho, in the West Bank, and Catalhoyuk in Turkey. We built structures meant for long-term habitation, houses. We used more permanent materials— stone, clay bricks. These buildings could last many years, even generations. They were larger than the little huts of hunter-gatherers. They were often built close together. And these settlements housed hundreds, sometimes thousands of people. They were permanently inhabited, for hundreds or thousands of years.

These were the first towns and cities.

A Bushman village. Villages were small, a few dozen people, living in grass huts which could be built in a day, and abandoned when the group moved.

Today, most of humanity lives in towns and cities. These range from a few hundred people to tens of millions— the metropolitan areas of Tokyo, Delhi, Shanghai, Cairo, Sao Paolo and Mexico City each have more than 20 million people.

We live in cities for various reasons —jobs, arts and culture, lifestyle. But the architecture of the earliest cities suggests they served a different purpose — for defense in time of war.

New York

Jericho — The Walls Came Tumbling Down

The modern city of Jericho lies in the West Bank of the Palestinian territories, where it’s currently administered by the Palestinian Authority. Over the years this place has been ruled by many powers. Egypt, the Canaanites, the Israelites, the Babylonian Empire, the Persian Empire, Alexander the Great, the Kingdom of Judea, Rome, the Crusaders, the Byzantine Empire, the Ottoman Empire, Britain, Jordan, Israel, Palestine. For a time, Jericho was even owned by Cleopatra, its oases and pools a gift from her lover Marc Antony.

New Jericho (background) and old Jericho (foreground)

A lot happened here. Here, it’s said, atop the mountain above Jericho, Satan offered Jesus the whole world, and Jesus refused.

There have also been many Jerichos over the years, cities that rose up from the desert to be occupied or destroyed by conquerors and abandoned. The most famous Jericho is the one supposedly conquered by Joshua.

According to the Bible, when the Israelites crossed the Jordan and invaded Canaan, Joshua’s army marched around the walls of Jericho for seven days, carrying the Ark of the Covenant, the holy artifact containing the tablets of Moses, with the Ten Commandments. On the seventh day, Joshua’s army blew their trumpets. The walls fell, and so too did Jericho:

“So the people shouted when the priests blew with the trumpets: and it came to pass, when the people heard the sound of the trumpet, and the people shouted with a great shout, that the wall fell down flat, so that the people went up into the city, every man straight before him, and they took the city.

And they utterly destroyed all that was in the city, both man and woman, young and old, and ox, and sheep, and ass, with the edge of the sword.

And they burnt the city with fire, and all that was therein: only the silver, and the gold, and the vessels of brass and of iron, they put into the treasury of the house of the Lord.”

Today ancient Jericho’s remains can still be seen. Its junk and debris form a tell, a large, misshapen, artificial mound of dust and human detritus. All over the ground are bits of chipped stone, broken pottery, brickwork (humans create a great deal of debris- human settlement is almost like geological process, one that results in very rapid sedimentation). These remains piled up over millennia, the debris and refuse of each Jericho covering up the last, with all the beauty and glory of a landfill. Where archaeologists have trenched through the layers of debris, you can see the rectangular red shapes of ancient clay bricks, and between them, grey lines of the mortar.

The walls of Jericho

The brickwork walls of Jericho are sad looking things, slumped and deformed, weathered by years of erosion, by time itself. The walls appear to have collapsed just as told in the Book of Joshua. Perhaps it was the work of an earthquake, or perhaps the hand of God.

Another view of the brickworks of the walls

A thick black layer, charcoal, marks where a fire raged through the city, destroying it. Again, this corresponds to the story of Joshua. At least some elements of the Book of Joshua seem to be based on historical fact, but whether Joshua himself ever visited and conquered Jericho, or even existed, is less clear. The available evidence suggests the Israelites invaded at some later date, so perhaps the Bible is combining two separate stories- the destruction of Jericho, and the conquest of Canaan.

The charcoal layer from the burning of Jericho

But archaeologists have dug down below the wall of Joshua’s Jericho, all the way to bedrock. Here they find other layers, other Jerichos, and other walls. The lowest and therefore oldest walls date to 8,300 BC, or around 10,000 years ago. This is around 2,000 years after the end of the last Ice Age. This makes Jericho among the oldest known cities in the world.

And it already has city walls.

When we think of civilizations like Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece and Rome, we think of wonders like the temple of the Parthenon, the palaces of Roman emperors, monuments like pyramids, sphinxes, statues, and ziggurats. We find none of these things at Jericho. Instead, in the lowest layers, in the first and oldest city we find walls.

Walls, and a tower.

The tower of Jericho

When Jericho was first excavated all the way down, in the 1950s, an ancient tower was uncovered. It is thirty feet across at the base, and rises twenty-three feet, tapering so that the top is just over twenty feet across.

The tower walls are ten feet thick. Instead of having rooms inside, like a medieval tower, there’s just a narrow tunnel, with a flight of steps. Maybe the builders lacked the sophistication to create something more complex; it is also possible that the thick walls were designed to resist earthquakes. The top of the tower is flat. Its possible this is just the tower’s foundation and that an upper structure of mudbrick or wood, offered cover or even supported another platform, for better visibility.

In addition to the tower, a stone wall ran around the ancient settlement. It is thought to have been about six feet wide, and twelve feet tall. The stone wall seems to predate the tower, and appears to have fallen down at least once, again perhaps due to an earthquake.

Jericho, then was a fortress.

The tall stone walls made it difficult to attack the settlement directly. Attackers either had to assault a few well-defended entrances, or somehow scale, or breach, the walls.

By the time of the Greeks and Romans, armies had sophisticated siege tactics to breach city walls, but when Jericho’s first walls were built near the end of the Stone Age, these hadn’t been invented. The attackers would have had weapons like bows, spears, clubs, daggers, maybe slings. Their arrowheads and spearpoints were made of stone. They didn’t have catapults and siege towers.

At the same time, one wonders why the walls were so high. Assuming the walls were efficiently designed (which may or may not be a good assumption), it seems the builders thought that walls six, eight, or even ten feet tall were insufficient to defend Jericho, and built them twelve feet tall. It’s possible that basic siege tactics— piling up stones, earth, or logs against the wall to create a ramp; using teams of men to ram logs against the walls to batter them down— were within the reach of the Stone Age people of the time, requiring relatively tall walls.

The tower could have served a number of purposes—perhaps it had a religious or ceremonial significance, or allowed priests or chiefs to address their people; it would have dominated the settlement. But one obvious purpose is military. Like the towers of modern castles, the stone tower of Jericho would have offered visibility; letting people watch enemy movements on the plains beyond the city, to shout warnings to defenders below. It offered an elevated point from which to shoot arrows, throw spears, or hurl stones. An extra twenty feet of height added range and momentum to missiles launched against the attackers below, while making it hard for attackers to launch missiles up at defenders.

Jericho’s construction marks a turning point in human history, the Neolithic Revolution. This is when humans switched from hunting and gathering, to farming and herding. It is also when we start building walls and defenses.

Farming comes with big advantages. Farmland can support far more people than hunting and gathering, since large swaths of land are given over to edible species, and eating plants transfers the plant’s energy directly to you, rather than first converting it to animal meat, which loses energy. As vegetarians are fond of pointing out, turning plants into meat and eating the meat is far less efficient than just eating plants. Because of that, in any ecosystem there are always fewer predators at the top than herbivores at the bottom. So as humans increasingly shifted from hunting, being predators, to farming, being herbivores, that meant more humans could live off the same land.

Farming also means you can settle and build, instead of moving with the seasons and following the wild herds. You can make permanent structures. You can accumulate possessions- millstones, pots, baskets, stone idols and altars, ceremonial knives- which is hard if you need to pack up and walk twenty miles to a new camp every few months.

But farming also created problems.

The Problem with Farming

Let’s say you work hard, planting wheat, barley, spelt and rye. Dyeus the Skyfather and Dhegom the Earth-Mother smile on you. Rains are good, harvests abundant. It’s a cold winter, but you have baskets of grain and dried meat. Not lots, but enough. But perhaps your neighbors are not quite so well-off and well-fed.

Perhaps they sowed too early and a frost killed their crops, or too late and the crops were killed by drought. Maybe a rust killed the wheat. Perhaps they’re just lazy and disorganized. But its winter, they’re hungry.

Or maybe they’re a herder tribe. Storms killed their sheep and goats, and they’re hungry.

Or maybe they’re hunters following the few remaining wild animals, after the herds have been mostly hunted to extinction. And they’re hungry.

Your neighbors arrive, reminding you how in better times you feasted together, and traded. They don’t speak of war. They don’t need to. They have bows, spears, daggers, faces wearing scars and hungry looks. Maybe you give your neighbors food, but it’s not enough. They come back for more, and there’s nothing left to give. Maybe they see other things they’re hungry for— pretty beads and stones, or pretty women. So they talk amongst themselves, and decide: these farmers, who have so much food and land— why not take these things?

By creating large concentrations of food, and goods, and people, we create problems, haves and have-nots. Like Bruce Springsteen sang in Darkness on the Edge of Town, “Well, you're born with nothing. And better off that way. Soon as you've got something, they send someone to try and take it away.”

What things the farmers own must now be defended; they must hold their ground and fight.

A key military advantage of hunter-gatherer cultures is their mobility. Under threat, hunter-gatherer tribes can break camp, move, and set up a new camp twenty miles away, in days. This makes hunter-gatherers difficult to attack, it’s hard to even to find them to attack. And if they are attacked, they can grab what few possessions they own, make a hasty retreat, and run. Farmers can’t make use of mobility, though.

Farmers have to stay near their fields to protect crops from destruction, and protect their food caches. If their fields are raided or burned, or granaries are raided and seed-corn stolen, they starve.

What’s more, being settled, their enemies always know where to find them- if not this year, next year, or the year after. They can wait for the right moment to attack. For instance, after an earthquake devastates their settlement, and knocks down the walls.

So settled farmers are vulnerable to the depredations and schemes of hostile tribes.

This creates a scenario like something out of a post-apocalyptic movie. In these movies, the real threat often isn’t the thing that ends civilization- zombies, nuclear war, asteroid impact, climate change. It’s the other survivors, the people fighting over the scraps in the ruins.

In one of the great classics of the post-apocalyptic genre, Mad Max: The Road Warrior, after civilization falls apart, a band of survivors build a walled compound around the last remaining oil pump. A hostile gang of bikers and assorted killers, lunatics, and post-apocalyptic scavengers, under the leadership of a hostile warlord, come to kill everyone and take the oil.

This is not unlike a scenario faced by early farmer settlements; except the raiders are instead after grain, not gasoline.

Mad Max: The Road Warrior

Without the state to control violence and mediate disputes, might makes right. You can only truly own something- your grain, your life- if you can defend it. We imagine the world after a nuclear war, when people are “bombed back to the Stone Age” and rebuilding civilization, would be a violent and lawless place. But this violent, lawless scenario also describes the late Stone Age, the Neolithic, when people were building civilization for the first time around.

Post-civilization and pre-civilization are effectively the same thing.

Both lack institutions like kings and presidents, courts and judges, military and police to prevent violence between or within groups. There’s no United Nations to broker and enforce a ceasefire. Both the post-apocalyptic, post-civilization wasteland and the pre-civilization Neolithic Revolution see groups of people pitted against each other for survival, fighting for food, land, and resources.

In a post-apocalyptic scenario, finding food is one of your first problems. After the societal collapse, if you survive, you’ll need to find some farmland, perhaps get a few sheep, some greenhouses. But once that problem is solved, it creates a second problem. You now have something valuable— stored food, farmland to grow more food— that other survivors want to take. Once you’ve got food and land, you need to defend it. This why survivalists are always into guns, of course. They may be wrong about the impending collapse of society, but they’re correct in assuming they’ll need to defend themselves if it does collapse. And this is also why billionaires create giant bunderground bunkers. They know that if there’s no state, there’s no one coming to defend their property, or their lives. They have to be able to defend themselves.

More or less the same scenario applies if you’re rebuilding civilization after a nuclear war, or building it from scratch after the end of the last Ice Age. No one is coming to save you, if you’re in trouble. You must defend yourself.

Your simplest means of defending a settlement is just numbers. If you gather enough people- say, a thousand people, with maybe half the men of fighting age– you now have several hundred fighters, a formidable force even in modern times. You’re relatively safe. The only threat is if you’re faced against a similarly large tribe, or several smaller tribes that, allied together, have enough fighters to overwhelm your fighters.

If so, you’ll need a way to even the odds.

Now you’ll need defenses— to tilt the odds back in your favor. Towers to spot enemies and rain missiles down on them; walls to defend your vulnerable people, to limit points of entry, and to allow defenders to maneuver and fire from behind cover. Clustering buildings creates a smaller area to defend, and lets an archer to cover a settlement from a tower or rooftop.

Catalhoyuk — An Ancient Fortified Compound

Were the first cities were built as fortified, defensive settlements, then?

It might seem like this is a lot to conclude from just one city, Jericho. But consider other early settlements. Catalhoyuk in Anatolia, in Turkey, dates to 7400 BC, about five hundred years younger than Jericho. Catalhoyuk is smaller, with perhaps a thousand people. Catalhoyuk lacks a city wall, but odd details of the settlement suggest that it’s not a simple city or town. It’s a fortress. The architecture isn’t sort of urban architecture we’re used to, with houses and shops and streets, but a fortified compound, specifically built to repel attack.

Excavation of Catalhoyuk.

Reconstruction of a Catalhoyuk house: note the roof access, and lack of windows.

First, let’s look at the houses. They’re rectangular mud-brick houses, much like modern houses in shape. But here the similarity ends. The houses have no windows. They have no doors. Instead, the only way in is to descend by a ladder through a hole in the roof.

Second, the houses aren’t spaced out with yards and gardens, or even streets between them. Instead they cluster together, packed literally wall-to-wall. To enter a house, you climb a ladder to the roof. Then you walk rooftop-to-rooftop until you come to your house, then climb down.

Catalhoyuk, Turkey

Reconstruction of Catalhoyuk

Another reconstruction of Catalhoyuk

Catalhoyuk, rather than being a quaint farming town in the country, is a walled fortress. While lacking a city wall like Jericho, the houses’ outer walls, packed edge-to-edge, become a city wall. To attack, you must climb up this wall to enter, and it can be secured just by pulling the ladder up. Even assuming fighters managed to get on top, people in the houses below could simply pull their access ladders down. To get at the inhabitants, you’d then have to jump down, or find a ladder to descend into an unfamiliar house where people would be waiting to attack you as your eyes adjusted to the dark.

The buildings at Catalohoyuk have also been reconstructed as multi-story. This would have increased the height of the walls further in places, and provided elevated positions for observing the enemy, firing on them, or dropping rocks on their heads.

Curiously, we see similar architecture in the Middle East today— walled compounds called ksars are common in places like Morocco, for example ;although these houses typically have small windows, and doors and streets inside the outer walls, they are overall very similar to Catalhoyuk.

Ait Ben Haddou, a Moroccan ksar

Perhaps the best modern parallel to Catalhoyuk is with the adobe dwellings of people like the Pueblo Indians of the American Southwest, where square, mudbrick houses are tightly clustered, and accessible from the roof. It is generally thought that the architecture of pueblo dwellings is defensive. They were often built along defensible positions, such as cliff edges, making them harder to attack.

An Anasazi pueblo

Another thing that makes Catalhoyuk defensible is location. A river to the back of Catalhoyuk created a natural moat. Fording even a shallow river slows attackers. Even modern armies struggle to cross rivers (after the Russian withdrawal from Kherson, the Russians blew the bridge across the Dnipro, and since, neither side has been able to mount an effective offensive across the river). If there were fords or bridges across the river, they constrained where an attack could come from. Simple bridges made of logs or planks could have been used in times of peace, but pulled across in times of war.

Amnya River, Siberia

A third archaeological site supporting the idea that fortification was important in the development of early settlements is the Amnya site, in western Siberia. Here a settlement was built about 8,000 years ago, with a series of ten pit-houses being built on a tall, triangular bluff. The site was effectively impossible to attack from the south, west, and north because of the steep bluffs. The eastern approach was guarded by ditches and palisades.

Curiously, the Amnaya people weren’t farmers, but hunter-gatherers. Presumably, they were organized enough to gather or hunt enough food to settle down for long periods, if not year-round, then perhaps for the winter. They may have cached food in the form of dried or frozen meat, dried or smoked fish, fish oil, and soforth. Those food caches would have been tempting to rival tribes, and had to be defended from raiders.

Amnaya is interesting because it suggests an alternative path to the creation of long-term settlements— one that doesn’t rely on farming. And yet this path to settlements still involved the creation of fortifications. Settled communities create the risk of attack- and the possibility of defense- whether they get their food from farming or fishing. And so different pathways towards permanent settlements frequently have converged on creating defensive fortifications.

Historic times

Finally, we see societies from historic and modern times, the past few thousand years, with relatively low levels of social complexity (comparable to Neolithic communities like Catalhoyuk) which never the less build defenses.

The Korowai tribe of New Guinea build houses in trees where they are difficult to attack.

The Dani tribe of New Guinea built watchtowers out of wood, to keep eye out for enemy attacks.

The Maori tribes of New Zealand fought each other ferociously, and to defend from attack, they built sophisticated, fortified villages called Pa.

A pa, a fortified Maori village

The Mound-Builder cultures encountered by Spanish explorers in the Americas in the 1500s were defended by palisades, as were Iroquois villages encountered by early American colonists. As we’ve already discussed, the pueblos of Southwest indians were designed to be highly defensible, and sometimes placed on cliffs to make them harder to attack.

In Alaska, the Koniag people of Kodiak made use of steep-sided islands as natural fortresses to keep women and children safe during times of war. The most famous of these was Refuge Rock in the Kodiak archipelago. This was the site of a massacre of Koniags by the Russian fur traders under Shelikov, after the Koniags evacuated to the island to try to protect themselves from the Russians.

Refuge Rock, off the coast of Sitkalidak Island, Kodiak Archipelago, Alaska.

In the Iron Age, Celtic tribes in Britain made extensive use of defensive architecture. One of these fortified settlements is found at Solsbury Hill, near Bath. Here, extensive ramparts made of stone would have been about 12 feet tall and 20 feet wide; the steep flanks of the hill itself made the walls difficult to approach on most sides. Houses were built on the flat top of the hill inside the walls, but eventually burned down in the 1st century AD.

Map of Solsbury Hill

British hill-forts also made use of islands, like the Alaskan natives did. The little tidal islet of Burry Holmes, in Wales, was bisected by a ditch-and-palisade. This guarded the eastern approach to the islet; the south, west, and north sides of the islands are vertical rock cliffs, making an almost impregnable fortress.

Another form of defensive settlement was the crannog— settlements on artificial islands in lakes. One of these is found in Glastonbury. At the Glastonbury lake village, about 200 people built houses on artificial islands in the middle of a lake, surrounded by water and wooden palisades.

it seems that in many fairly small, simple primitive settlements, although lacking things like complex governments, organized religion, or monuments, there are never the less defensive structures.

The Role of Warfare In Urbanization and Civilization

My argument isn’t that war alone explains everything about the emergence of cities. Modern cities serve many purposes— they’re centers of socialization, trade, finance, manufacture of goods, religion, government, entertainment and art, etc. The same was likely true of early cities. I wouldn’t necessarily go so far as to argue that all early settlements were defensive in nature.

But war was a major factor, one deserving more attention.

Agriculture forces people to stay in one place for long periods of time to till the soil, sow, reap, to defend their crops and stores. Food caches and granaries make you a target. So settling down to farm made people targets for attack in a way they hadn’t been before. This required defenses.

The need for Stone Age farmers to defend themselves encouraged them to settle together in large, densely populated settlements that were easier to defend, rather than in sprawling settlements. It encouraged people to create city walls, towers, fortified compounds, palisades, ditches, moats, and live behind them.

The Aurelian walls, Rome

So I don’t claim that war explains everything about the emergence of cities, just that it’s an important and perhaps underappreciated factor. War may be an accelerator of the process of creating large cities and civilizations, helping to drive people into large, dense, permanent settlements. This probably also forced some minimum degree of organization, coordinated by a leader- a chief, a shaman, or a king of sorts. Catalhoyuk, which seems to lack an overall plan, may have emerged more organically, families may simply have chosen to build houses close together, one at a time. The relatively similar size of the houses suggests limited hierarchy, no lords or kings. But in Jericho, someone probably had the power to coordinate building of the towers, and the walls.

Cities would have doubtless emerged sooner or later, for all the other reasons cities exist. But war likely accelerated the process, making settlements larger, denser, and more organized, more quickly than they would have otherwise. People moved to cities and behind walls, because they were safer there than outside the walls. War likely accelerated this trend, like it accelerated other developments. In WWI and WW2, the development of fighter and bomber planes helped push the development of air travel and air transport. Codebreaking computers helped accelerate the computer age. The desire to lob ballistic missiles at each other gave us space travel, space telescopes, satellite internet. Making communications networks robust to Soviet nuclear strikes was a major reason the internet was developed. In the same way, war may have helped make cities.

More broadly, I think war helps explain a peculiarity of the human species— why we form large groups at all. Chimpanzees live in groups of a few dozen. While simple hunter-gatherer societies like the Bushmen and Hadzabe typically live in small bands, anywhere from 10 to 60 people, these ally into larger organizations- tribes. These tribes can include a thousand people, united by language, religion, customs, and ties of marriage, friendship, and trade. What’s the purpose of such a large social group? I’d argue it is to hold territory; a thousand people working together can defend a piece of land far better than fifty- or, for that matter, more easily conquer their neighbors’ territory.

This may be a major driver of social complexity. Tribal farmers and herders can form even larger groups, with thousands of people. Later, we see the emergence of city-states, kingdoms, empires, with hundreds of thousands, or millions of people. Bigger groups tend to emerge over time, because they can defend themselves, and acquire more land. Smaller groups are easily wiped out or absorbed into bigger groups. This creates a sort of arms race in terms of the size and complexity of social groups; bigger groups tend to fare better in war.

The emergence of cities, then, is just one small part of a much bigger problem- how the pressures of warfare have shaped human social structures, our tribes, and civilizations.

It all Begins with Walls

Defenses are often one of the first things people build when they settle down.

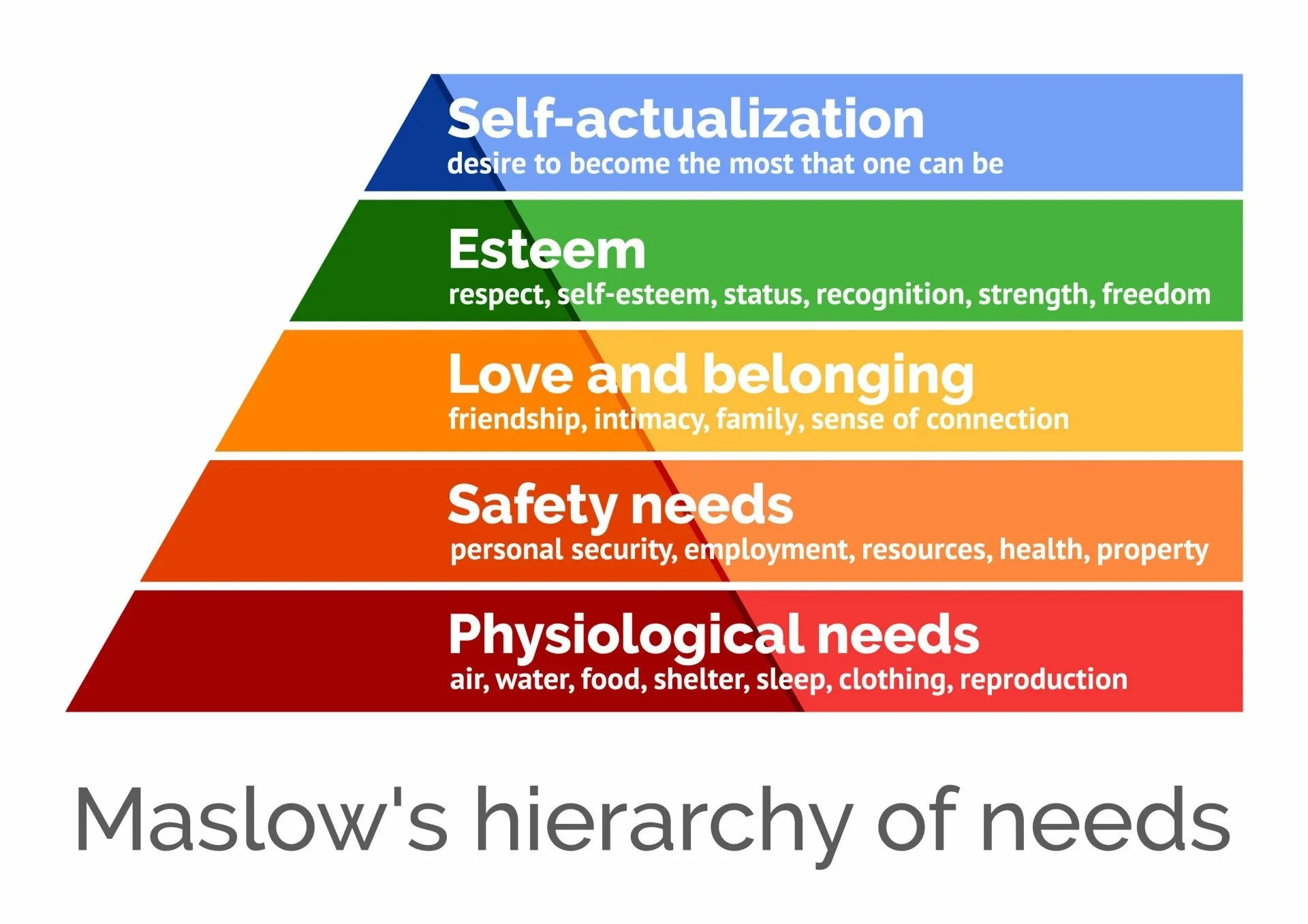

In terms of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, physical safety is very low on the hierarchy and therefore defense is likely among the first things a settled culture will focus on.

The one place I would disagree with Maslow is that arguably, safety needs to go at the bottom of the pyramid. Think about it.

You can freeze in a night. You can die of thirst in a few days. You can starve in a matter of weeks.

But a lion can kill you in seconds. So can a hostile outsider armed with a bow, a spear, or a club. You can have food to last through winter but you’re not going to live long enough to eat it, if someone shows up to kill you and take it. Before anything else, a settlement must first be safe. That’s why we so often see walls, palisades, towers and ditches appear early, and in primitive settlements that have almost none of the other elements of civilization. Civilizations can survive without theaters, palaces, and churches, they are unlikely to survive long without some form of defense.

Consider ancient Athens- long before the Parthenon was the site of the Acropolis, it was an ancient hill-fort, defended by massive walls built of huge stone blocks- “Cyclopean walls” (according to legend, they were built by the giant one-eyed Cyclopes). The Cyclopean Walls date to the late Bronze Age, around 1200 BC, about the time of Joshua’s Jericho.

Before math, philosophy, epic poetry, theater, architecture, democracy, all the stuff that the Greeks are credited with giving to Western civilization, the Athenians first created strong defenses. Literally and metaphorically, the Parthenon is built atop the city’s military defenses.

Civilization may start with walls.