Artwork,

Some pieces commissioned for research projects, some of my own.

I sometimes do my own art. I’ve been drawing since I was a child, I drew comics in high school, and when I was a grad student, I took a course from an art school. I’ve also been privileged to work with extraordinary artists like Andrey Atuchin, Raul Martin, and Julius Cstonyi. They’re far more skilled than me, but I’d like to think years doing art and illustration taught me a few things about the craft and so, like a movie director knows how to get the most out of his actors, I know how to get the most out of them. I’m biased, but the pieces I’ve commissioned are among my very favorite works of scientific art.

For the longest time, I saw an artistic side as incompatible with serious science. Science, I thought, was all about rigid and formal writing. It was huge volumes of data and rigorous mathematical analysis. It was complex graphs, computer code, and so on. Being a scientist required doing science to the exclusion of other things. Scientists were, well, all science. I don’t know where I picked this idea up. I think it has to do with the fact that there’s lots of posturing in academia — you’re constantly auditioning for grad school, a postdoc, a job, a promotion. So people try to present themselves as serious academics and serious people, it becomes performative. Instead of just being scientists, it’s like they’re cosplaying the stereotypical scientist… and in their mind, scientists just do science.

Yet, it’s likely that doing art helps with being a scientist. Historically, great scientists often had creative pursuits. Einstein had his violin, Oppenheimer wrote poetry, Feynman had his drawings and his bongos but perhaps more importantly his writing, Darwin was as much a writer as he was a scientist; Galileo was arguably the first popular science writer. That may be because science is a creative pursuit, one that requires imagining solutions to problems no one else has thought of, and that exercising your creative faculties through music, writing, acting, poetry lets you see and imagine different possibilities, it develops imagination. So arguably, if you’re truly serious about science, you need to be doing something creative. These days I tell my students to keep their creative pursuits— keep drawing, acting, dancing, writing. It makes your science, and your life, richer. Studying ancient rock art in Africa, a thought struck me — Homo sapiens was far and away the most talented artist of all the human species, and that may help explain why we survived, and the others went extinct.

Coahuilasaurus lipani, by C. Díaz Frías, 2023

The mosasaur Khinjaria acuta hunts Enchodus libycus. Andrey Atuchin, 2023.

The Moroccan duckbill Minqaria bata studies the carcass of the mosasaur Thalassotitan. Raul Martin, 2023.

Nanotyrannus attacks a young T. rex. Raul Martin, 2023

Vectidromeus insularis. By Emily Willoughby, 2023

Abelisaurids from the latest Maastrichtian of Morocco, North Africa. Andrey Atuchin, 2023.

Stelladens mysteriosus, a mosasaur from Morocco. Nick Longrich, 2023

Giant dinosaurs through time. Nick Longrich, 2022. For a popular article in The Conversation.

Thalassotitan atrox, a giant predatory mosasaurid from the late Maastrichtian of Morocco, preying on a Halisaurus. Andrey Atuchin, 2022.

Thalassotitan atrox holotype, by Magdalena Cygan, 2022.

A freshwater plesiosaur from the Kem Kem of Morocco, by Andrey Atuchin, 2022.

Vectiraptor greeni. Gabriel Ugueto, 2021. A large-bodied dromaeosaur from the Isle of Wight.

Early Paleocene snake, by Joschua Knuppe, 2021. Based on a concept sketch of mine. I said I wanted something that looked like it could be on the cover of a heavy metal album, or a tattoo on the arm of the bad guy in a Lethal Weapon movie.

Art for a popular piece on prehistoric drug use, Nick Longrich, 2022. The drawings are traced from my photos of cave art by Sandawe and Bantu in Kondoa and Hadza in Eyasi, as well as drawings from the literature by pygmies and bushmen. The silhouette is a Hadza hunter, whose bow has been replaced by a spear.

The mosasaur Pluridens serpentis, by Andrey Atuchin, 2021. Pluridens has small eyes suggesting it foraged in low-light conditions using non-visual cues like the tongue and mechanoreceptors. It is made to look a bit like a deep-water shark, the sleeper shark, going after a deep water cephalopod, a vampire squid, and hunting with its tongue. It sort of riffs on the classic sperm whale versus squid scene.

The mosasaur Xenodens calminechari by Andrey Atuchin, 2021. A scavenging scene. Very whale-like mosasaurs, because why not?

The duckbill dinosaur Ajnabia odysseus, by Raul Martin, 2021. A coastal scene in Morocco, with palm trees. The white sands, deep blue waters and palm trees are inspired by a trip to Polynesia.

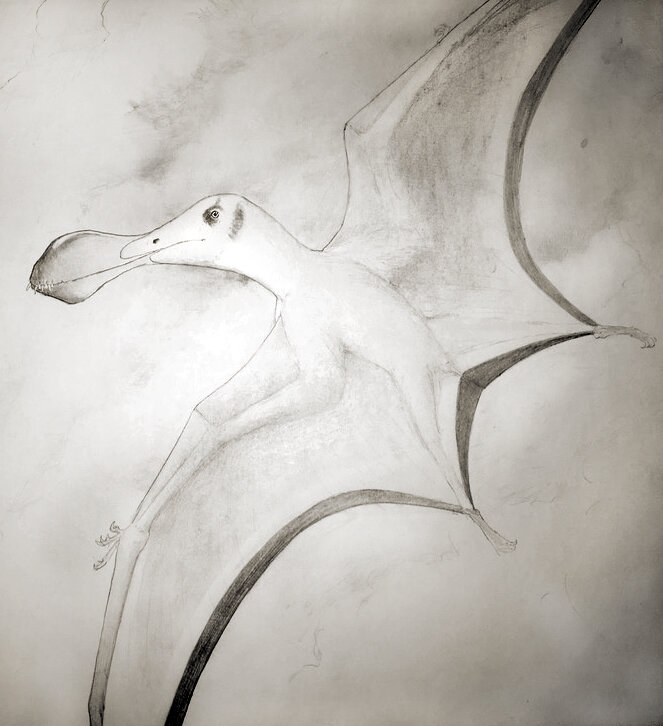

The long-snouted pterosaur Leptostomia begaa. Nick Longrich, 2020.

Coloborhynchus fluviferox, Nick Longrich, 2019. A pterosaur from the Late(?) Cretaceous of Morocco.

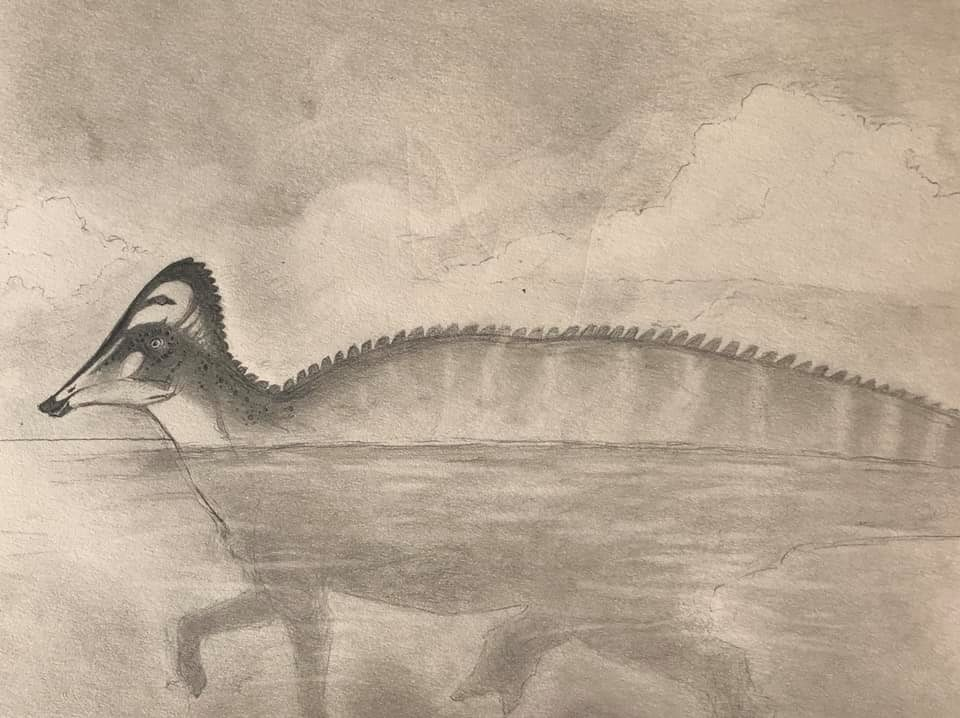

Oceangoing duckbill Ajnabia odysseus, Nick Longrich.

Chenanisaurus barbaricus, Nick Longrich 2017. A large abelisaurid from Morocco.

Tetrapodophis amplectus by Julius Cstonyi, loosely based on my concept sketch. Early versions were a little too freaky (the mammal was struggling desperately) so it was downplayed to have the mammal slowly drifting off into unconsciousness.

Archaeopteryx lithographica, by Carl Buell. Based on extensive study of the Berlin specimen, this Archaeopteryx includes a number of archaic features- long coverts covering the primaries, a tail fan extending up to the hips, flight feathers on the limbs. Fingers and toes are not scaled but fuzzy, as in dromaeosaurs from China.

Late Maastrichtian lizards and snakes, Carl Buell, 2012. For a paper on Cretaceous-Paleogene lizard extinction.

Pentaceratops aquilonius, Nick Longrich, 2014. From a paper on chasmosaurines from the Late Cretaceous of Alberta, Canada.

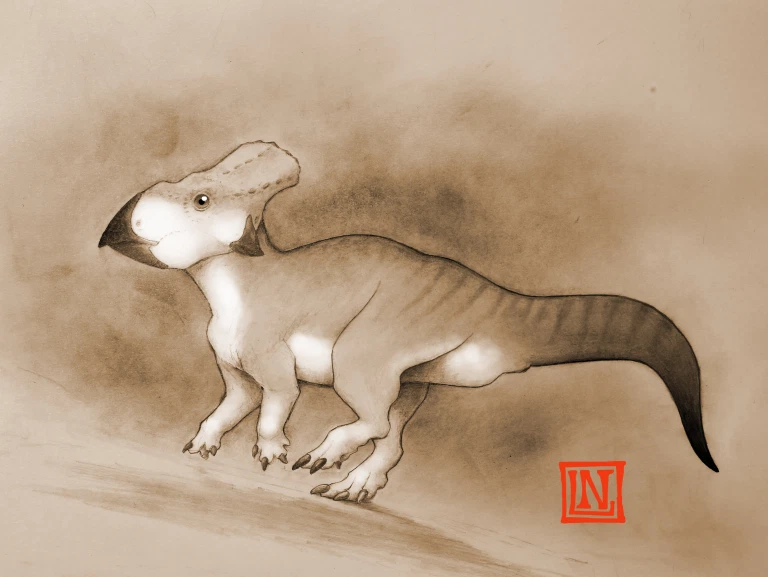

East Coast Leptoceratopsid, Nick Longrich, 2016. From a paper on a fragmentary ceratopsian specimen from the Late Cretaceous of North Carolina.

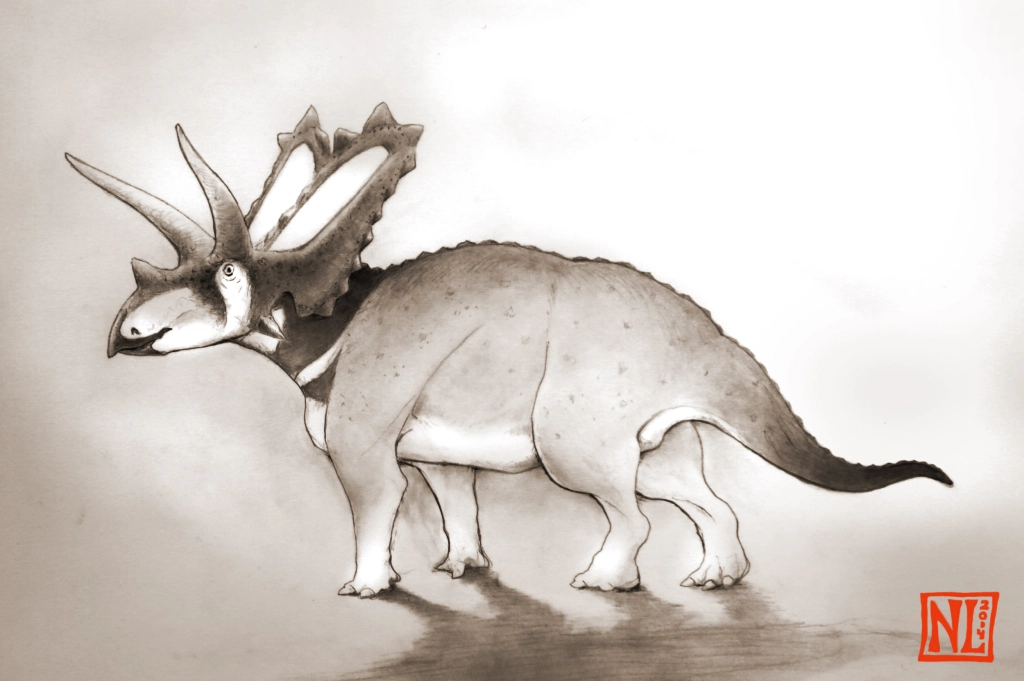

Judiceratops tigris, Nick Longrich, 2013. A new chasmosaurine from the Campanian aged Judith Creek Formation of Montana.

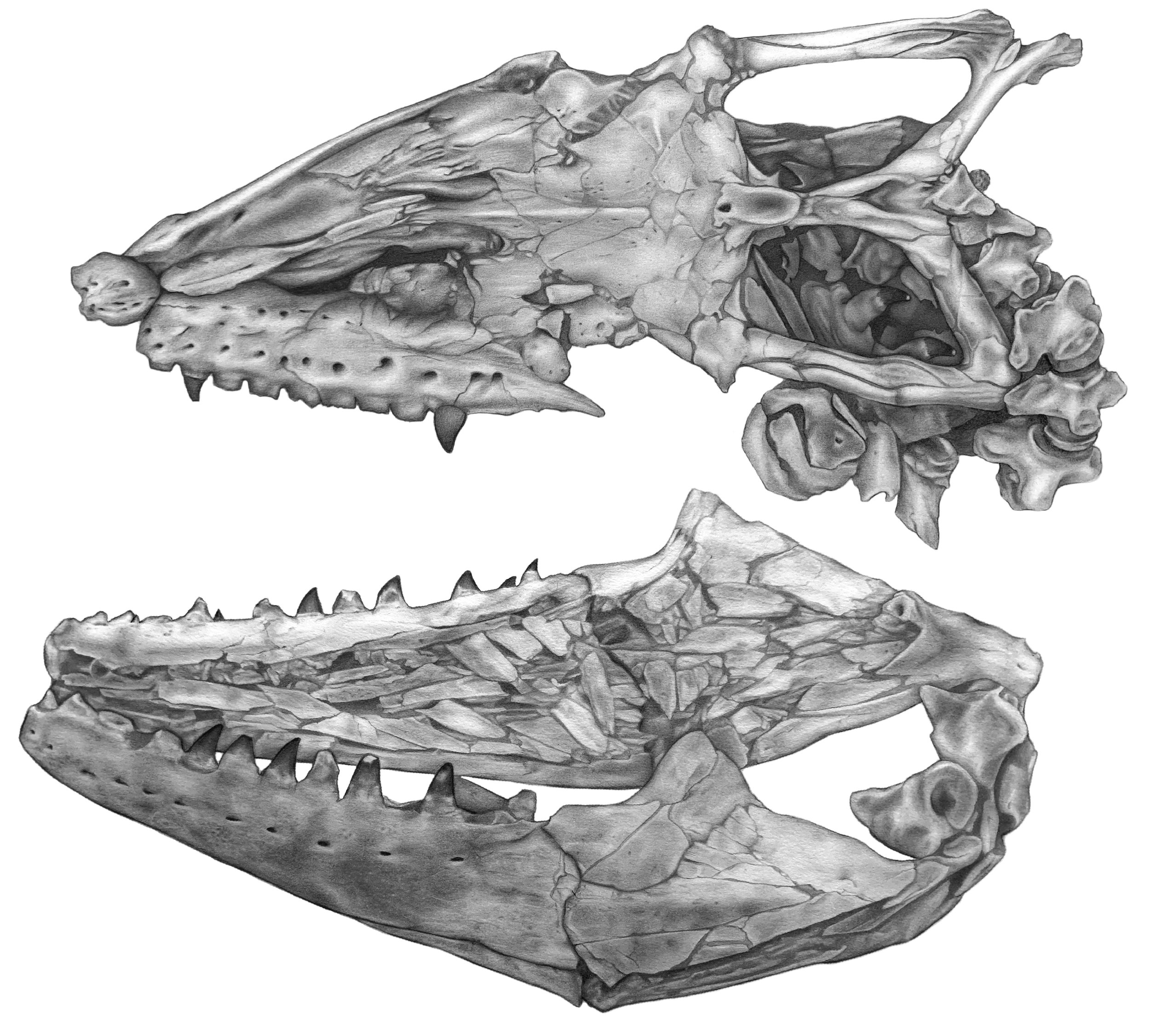

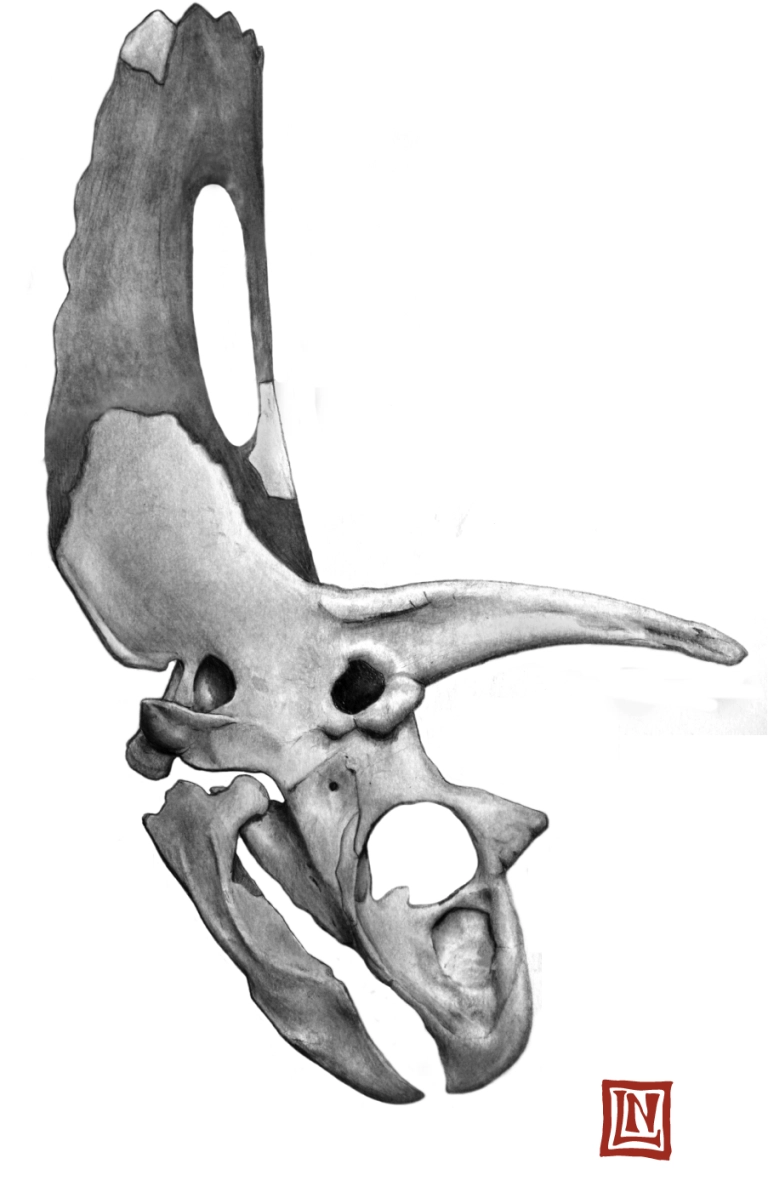

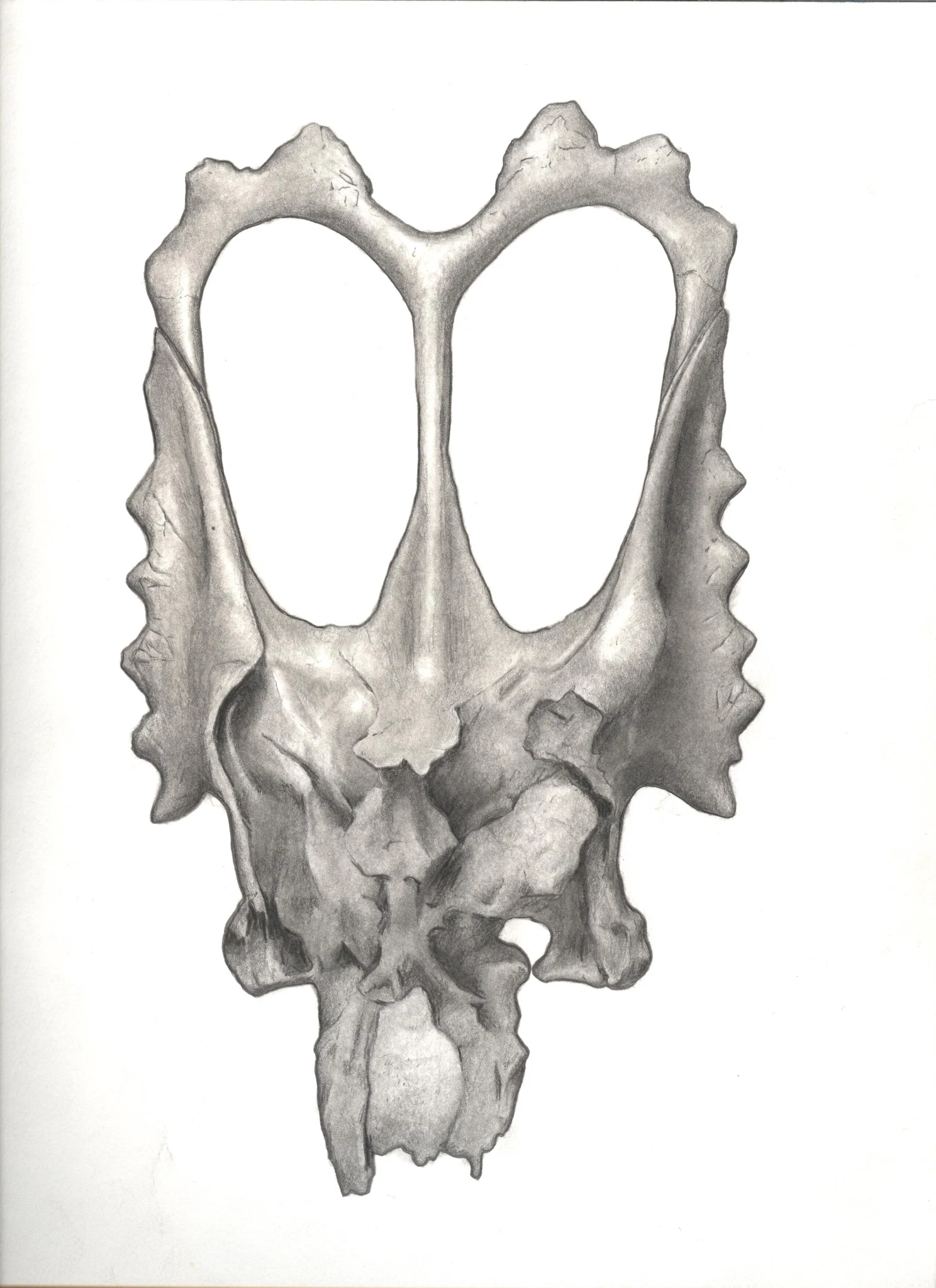

Titanoceratops skull, Nick Longrich, 2011. The holotype of the giant triceratopsin, Titanoceratops ouranos, from the late Campanian of New Mexico.

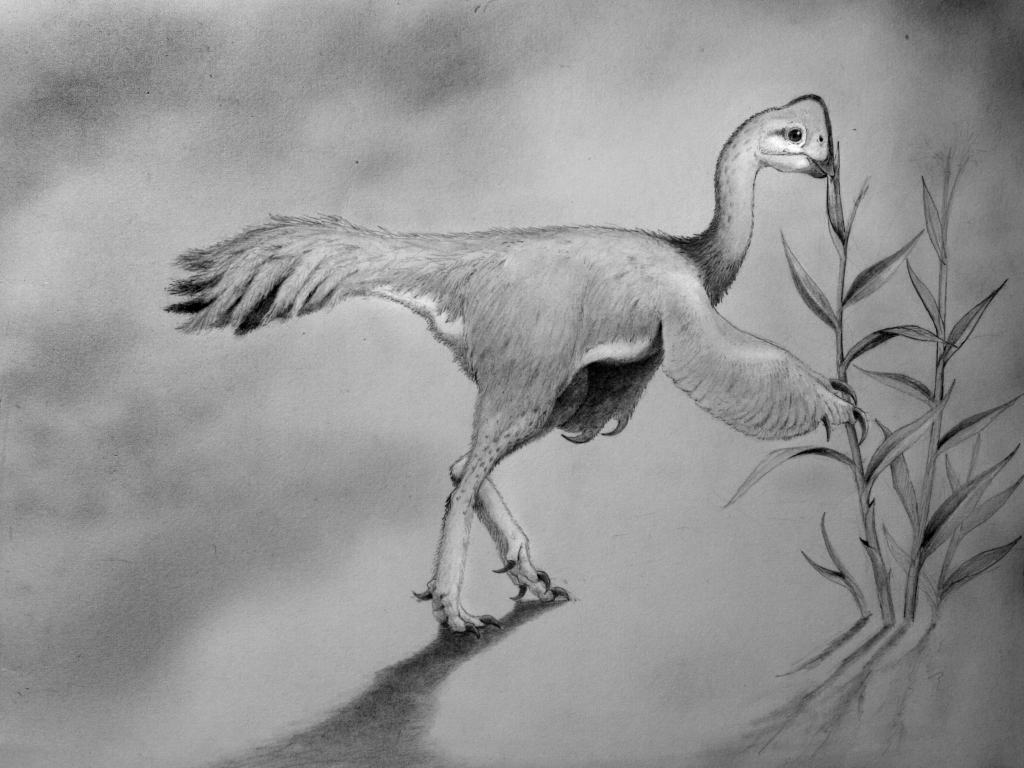

Leptorhynchos gaddisi, Nick Longrich, 2013. A birdlike caenagnathid from the Campanian of Texas.

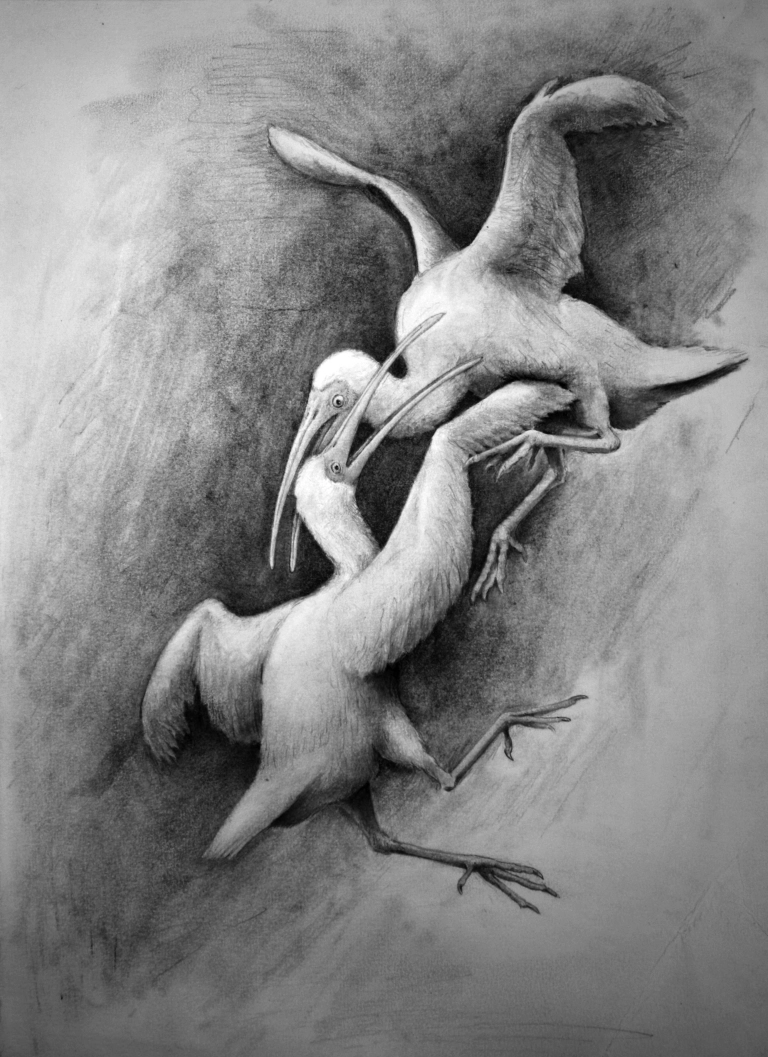

Xenicibis xympithecus, an extinct, flightless fighting ibis from Jamaica, Nick Longrich,

Mojoceratops (referred skull), Nick Longrich. A chasmosaurine ceratopsid from the late Campanian of Alberta, Canada.

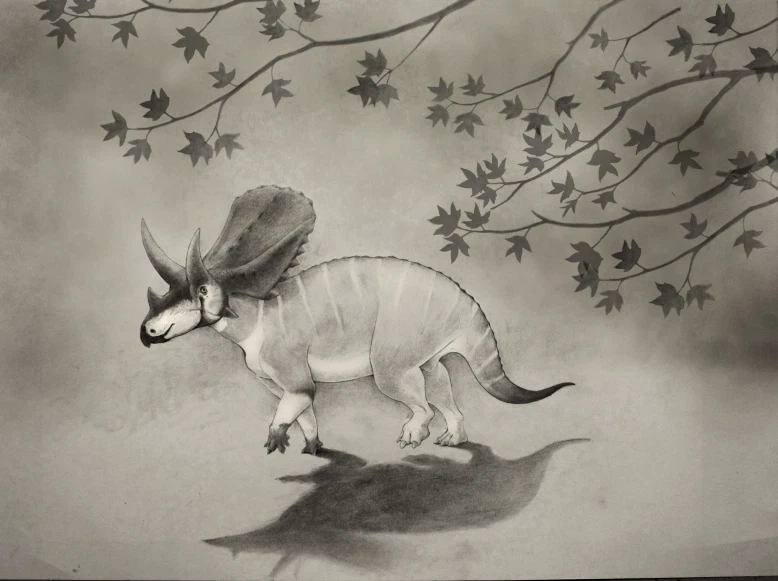

Mojoceratops perifania, Nick Longrich.

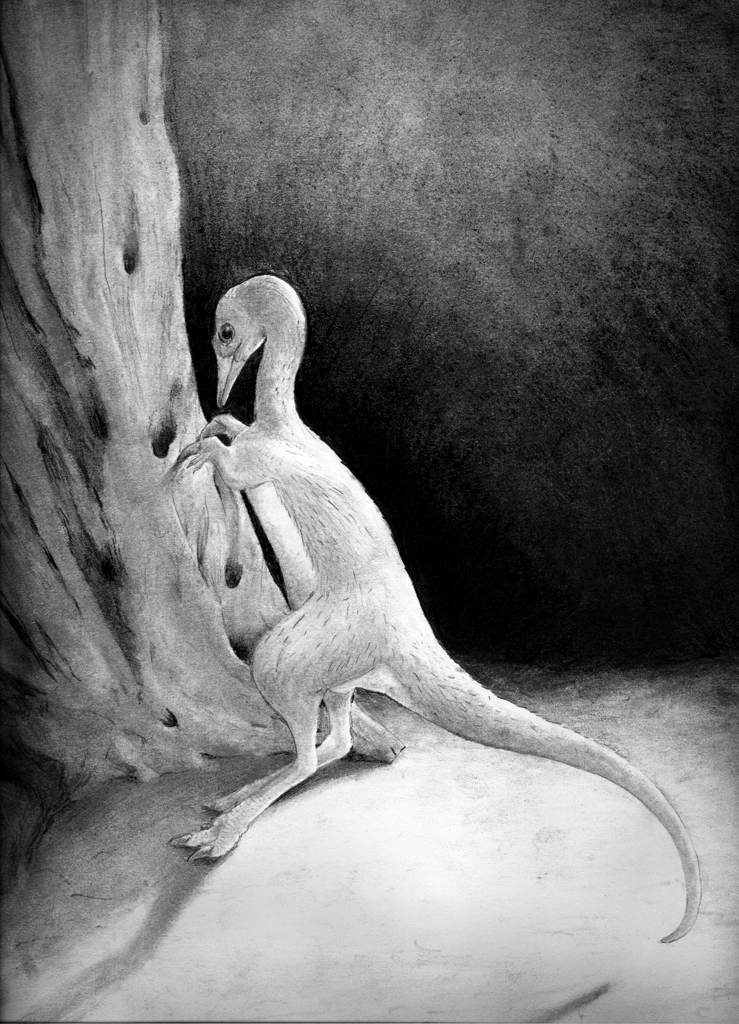

Hesperonychus elizabethae, Nick Longrich, 2008. The little dromaeosaur Hesperonychus, from the late Campanian of Alberta, Canada, one of North America's smallest dinosaurs.

Hesperonychus elizabethae, Nick Longrich.

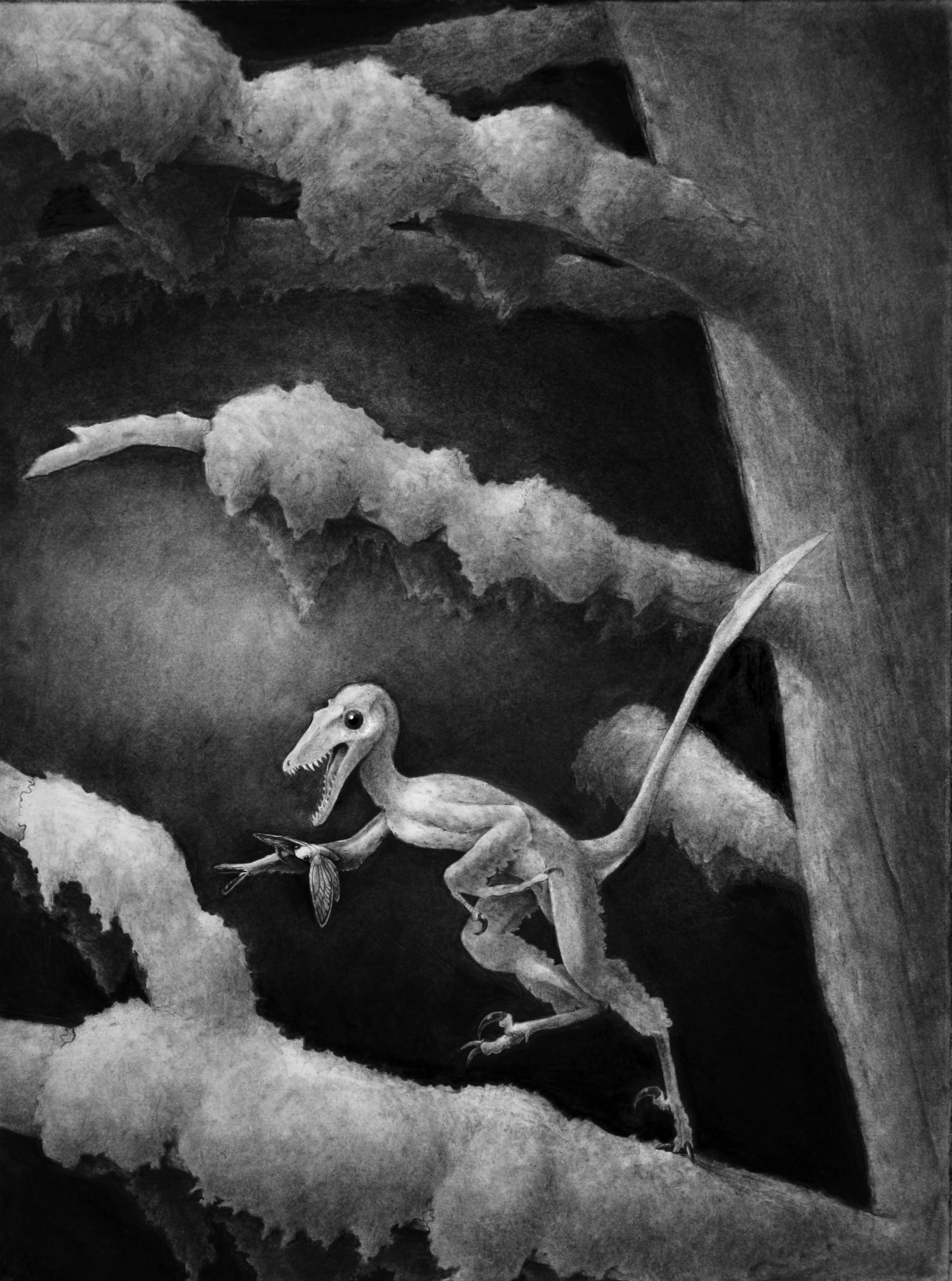

Albertonykus borealis, NIck Longrich, 2009. An insect-eating alvarezsaurid from the early Maastrichtian of Alberta, Canada.

Archaeopteryx lithographica, Nick Longrich.