The Discovery of Titanoceratops ouranos

“Huh, that’s funny.”

A lot of scientific research begins with those words, or else, the less civil “WTF?”

The giant “Pentaceratops” on display at the Sam Noble Museum in Norman, Oklahoma

In describing Mojoceratops, something strange happened. In attempting to enter the data for its relative Pentaceratops, the animal’s anatomy was difficult to code. The problem was that Pentaceratops was a highly variable animal- anatomical features present on one specimen weren’t present on another. In fact, it seemed bizarrely variable, and this largely came down to a single, very unusual, very large skeleton, one that seemed rather out of place. This skull, Oklahoma Museum of Natural History (OMNH 10165) Oklahoma’s Sam Noble Museum, simply did not look like any other Pentaceratops known. And in fact, it looked a lot more like Triceratops, and the only parts that actually did look like Pentaceratops- the characteristic ‘butterfly’ hornlets on the midline of the frill- weren’t real bone. They were just sculpted out of plaster.

All dinosaurs are different, of course, like snowflakes. Even within a single species, no two horned dinosaur skulls are exactly alike (neither are any two human skulls). Each dinosaur had a unique DNA sequence, and a unique life history. They all developed differently, due to environment, diseases, and soforth—they grew differently just like the crystals of a snowflake.

Horned dinosaurs in particular tend to be pretty variable in terms of their size, the length and shape of the horns, even the left and right sides of a single skull can have different number of hornlets on the frill. In general, structures under strong sexual selection (as the horns and frills probably were) tend to vary a lot. But within a species, animals tend to resemble one another in a general way, and in certain less variable details of their anatomy; if they’re not identical, they’re variations on a theme, drawn from the same gene pool.

But this Pentaceratops was unusual. It just didn’t look even remotely like the others. I sometimes joke that a lot of paleontology is like the old bit from Sesame Street— one of these things is not like the others, one of these things doesn’t belong.

OMNH 10165, skull and illustration, showing reconstructed frill (in black). The hornlets on the back of the frill curve forward like in Pentaceratops, but this piece is plaster reconstruction- not real.

The most obvious difference was that the animal was enormous. It was pushing 7 tons- well over twice as big as a typical Pentaceratops and close to the huge Triceratops in size, which made it one of the largest known horned dinosaur skeletons. Even setting the extreme size of the animal aside, there were all these unusual, Triceratops-like features:

Brow horns. The brow horns were huge, strongly curved forward, and had massive bases filled with a huge sinus, or air space, which was far more like Triceratops than Pentaceratops.

The nose. The nostril was elongate, extending well back over the maxilla, and the premaxilla was elongate as well. The inside of the premaxilla had a huge, elaborate sinus system, which extended down into the bone. Again, unusual for a Pentaceratops, but typical of Triceratops.

Nose horn. The nasal horn was positioned far forward, at the front of the nostrils. Again, you don’t get that in Pentaceratops usually. You do find it in Triceratops.

The upper jaw. The maxilla was extremely tall, almost as tall as long, as in Triceratops and Eotriceratops.

The frill. The scallops on the frill were very low, like in Torosaurus or a mature Triceratops; the central bar of the parietal was a thin, keeled plate, rather than a rodlike structure as in Pentaceratops.

The paper originally describing this skeleton, after listing a lot of ways that this skull was unusual for Pentaceratops (but looked like Triceratops) argued that this was an extremely unusual Pentaceratops, and that the species was incredibly variable. It was a bit like reading a paper describing a bird, and the paper noted that this bird looked like a duck. It walked like a duck. It quacked like a duck. And then the paper said “this bird is a chicken.” I don’t want to criticize the paper overly- it’s an expertly done piece of description, and I could do little to improve on the description of the anatomy, and it was critical to figuring out what this animal was. It just got me wondering- what if the interpretations of the anatomy were incorrect?

What if it’s not a Pentaceratops– but something else entirely? If in its size, its nose, the jaws, its horns all looks like a Triceratops… maybe it’s actually related to Triceratops?

This seemed implausible, just because the animal was far older than Triceratops- Triceratops was late Maastrichtian, and this animal was late Campanian, maybe 8 million years older. It would mean that we’d missed millions of years of horned dinosaur evolution up until now- that these huge, highly advanced dinosaurs evolved a lot earlier than we thought. For me, it was a bit like finding out that actually, people invented 747s soon after the Wright Brothers flew. Maybe that’s a bit of an exaggeration; still, I didn’t expect something like this animal to exist at that time. My assumption was that enormous, Triceratops-like dinosaurs would have been discovered by now if they went back that far in time.

Still, the more I looked at the illustrations, the more I kept finding evidence to support the idea it was an early Triceratops relative, even a direct ancestor, and so decided to study the skeleton myself.

On the way from Calgary to start a postdoc at Yale, I detoured to Oklahoma. On the way, I vividly remember the rain pouring down and a thunderstorm lighting up the night sky in rural Nebraska, and as I drove south and east, I put on Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska. That night, I pulled off to the side of the road to camp and threw out my sleeping bag. For some reason- some instinct I still don’t understand- I decided to check my bed first. Shining a flashlight, I saw a little rattlesnake, curled up in his own back, a few inches away from where I’d put my pillow. I poked him with a climbing axe, and he slithered off into the dark.

After I got to Oklahoma city, I spent a couple of days photographing and clambering around the huge skeleton at the Sam Noble Museum. I also had a look at the bits and bobs in the collection, and photographed old notes associated with the skeleton. In the end, I walked away pretty confident that it wasn’t a Pentaceratops– it was an early relative of Triceratops and Torosaurus– a Triceratopsin.

It wasn’t just the skull that was Triceratops-like. Other elements, like the humerus and the ischium, were also more similar; the huge deltopectoral crest of the humerus looked like a Triceratops or a Torosaurus. The closer you looked at this thing, the less it looked like Pentaceratops, the more it looked like Triceratops.

Like other specimens referred to Pentaceratops sternbergi, OMNH 10165 comes from the badlands of New Mexico. Unfortunately, we don’t really know where this animal comes from, which is annoying if you’re interested in problems of biostratigraphy- when did various dinosaur species evolve, and become extinct?

Notes from the Oklahoma Museum of Natural History. Titanoceratops came from somewhere in that yellow box- an area of about 5 by 5 miles- 25 square miles.

Today it’s taken for granted that a cheap smartphone has GPS capabilities that can pin a location down to a few meters. But back in the day, people used a grid system on topographic maps, which was far less precise and accurate. So we don’t really know where this skeleton comes from.

That you could lose a quarry that contained an elephant-sized dinosaur might seem crazy, but badlands are labyrinthine. It is extremely easy to become lost and disoriented in the coulees and hoodoos- I’ve done it many times myself, and seen people with years of experience get lost in the badlands at Dinosaur Provincial Park. What’s more, this thing was collected the better part of a century ago. Erosion has gradually wiped away most traces of the quarry.

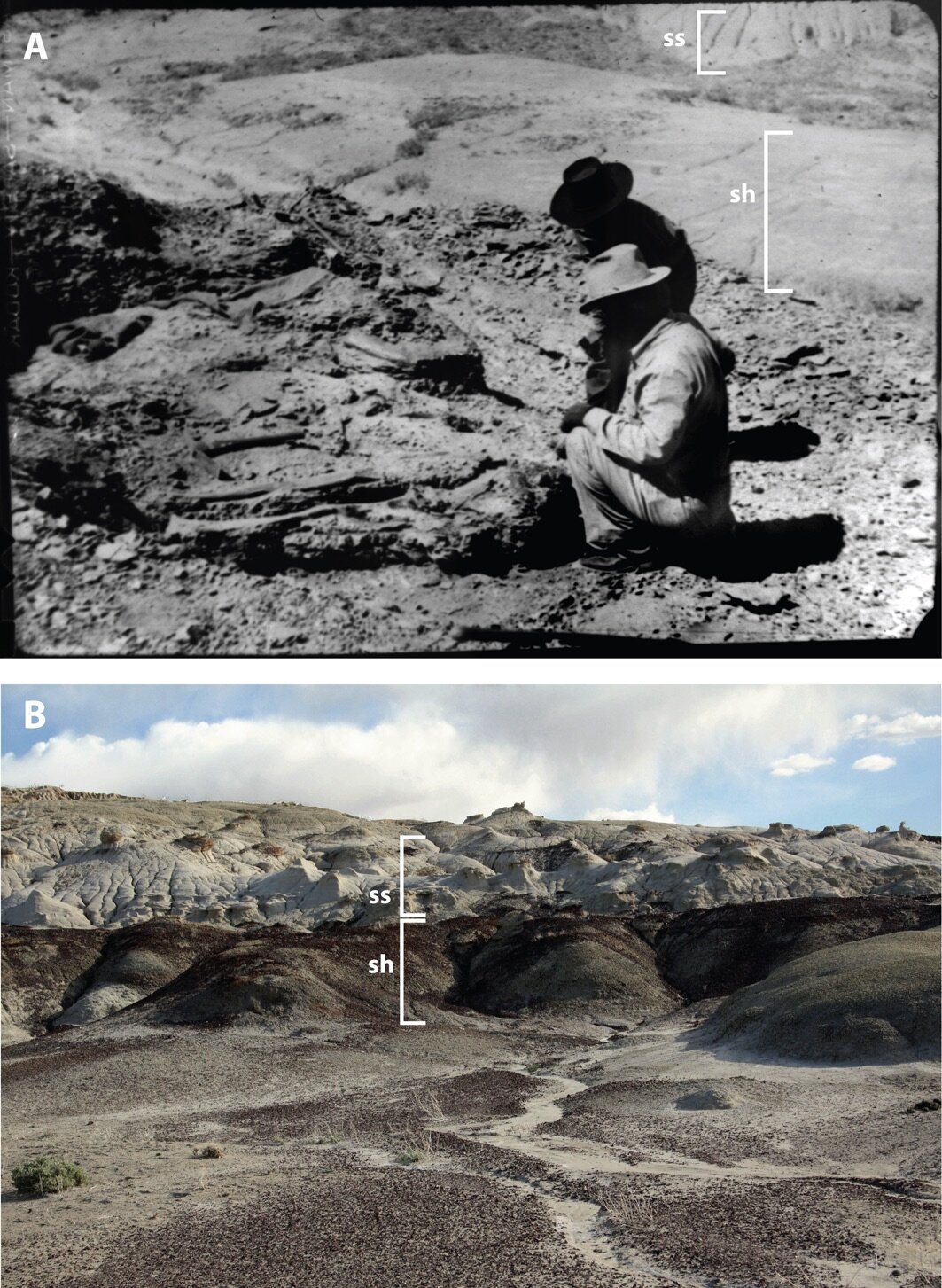

The specimen comes from either the Fruitland or Kirtland formations of New Mexico. Although we have photographs of the quarry, it’s proven impossible to relocate so far. The fossil comes from a fine-grained, organic rich sedimentary layer with little flecks of orange amber. I suspect it’s probably Fruitland but who knows. Hopefully someone can relocate the quarry- or another skeleton(!) someday.

In 1941, prolific fossil hunter Wann Langston was just a student- I assume this was him?

We have a few photos of the locality and excavation, but without knowing exactly where the thing comes from, trying to nail down the stratigraphy is hard.

The reason this matters is that there are Maastrichtian rocks out there in New MExico- where you would in fact expect to get Triceratops, or Triceratops-like dinosaurs. If the skeleton came from those rocks dating to 66 million years ago- the Naashoibito- it would be unsurprising to find a giant, highly advanced Triceratops-like animal.

However, the rock that produced the fossils is a fine, dark, organic-rich dark, with pretty little flecks of amber. This fits with other people’s assessment that the skeleton really is from the Fruitland/Kirtland. Despite its advanced appearance, it’s closer to 74 MYA than 66 MYA. The animal is ~8 million years earlier than Triceratops and Torosaurus at 66 MYA, and 6 million years before Eotriceratops at 68 MYA.

The implication is that giant Triceratops-like dinosaurs, the Triceratopsini, evolved in the Southwest. Later, in the Maastrichtian, they moved north into Wyoming, Montana, the Dakotas, and Canada. At this point, they became the dominant large herbivores.

Remarkably, Titanoceratops wasn’t hidden away in a museum drawer. It was a new species, in clear view. It was described in a scientific paper, and mounted for display in the center of a museum. The animal is about the size of an elephant, so it’s not exactly subtle. However, the assumption was that the animal was Pentaceratops, and the frill was reconstructed to make it look like one.

The lesson here is that people see what they expect to see, and tend to fit new observations into their pre-existing frameworks, or just ignore them, rather than change their minds. Most of what we’d seen from New Mexico was Pentaceratops, so this must be a Pentaceratops. Evidence that didn’t fit that was just overlooked. That effect is large enough to hide an elephant-sized dinosaur.

The animal was also reconstructed with plaster to reinforce that preconception- the distinctive notch and hook of the Pentaceratops frill were stuck on the back of the skull.

Objective observation of fossils is really, really hard. We like to be told we’re right. We don’t like to be told we’re wrong.

So we tend to focus on the facts that fit our ideas, and ignore the rest. It’s difficult to pay attention to facts that don’t fit your hypothesis, engage with them, and then change your mind. It’s harder to actively seek out evidence that proves you wrong- but this is what a good scientist does.

One of a scientist’s greatest strengths I think, is the ability to admit error and ignorance. To say, “wow, I really f***ed that up”, or “I have no idea what is going on here.” To be able to look at the data, and think, “huh, that’s funny.”

Being puzzled is a sign that the evidence doesn’t fit our expectations. That’s precisely when you need to sit up and take notice, and try to listen to what the evidence is telling you, and consider that maybe you’re wrong. Personally, I’m very open to the idea that I don’t know what the hell I’m doing.

I know I didn’t get this from my university education. That probably just made me more cocky and encouraged me to think I knew better than people who didn’t go to fancy East Coast schools.

Rather I think I got it from growing up around fishermen. As a fisherman, you have to be very open to the idea that you don’t know what’s happening. Where should you fish? How deep? What bait should you use? What’s the weather going to do tomorrow? What gear works best? Fishermen, I noticed, were anything but arrogant. They were very open to learning, in a way academics often aren’t, because there’s real stakes.

As an academic, you can get away with pretending you know everything. Once you have tenure, you can take a position, and never change your mind. In paleontology, you can often take a wrong position (e.g. “T. rex is a scavenger”) and stick with it simply because it’s so hard to definitively prove someone wrong in this field.

As a fisherman, this kind of arrogance can cost money, or your life. You have to constantly be open to the idea that you’re doing things wrong, and there’s a better way to do things.

Science isn’t about being right all the time. It’s about making mistakes, and learning from them. If you think you know everything, how can you learn anything new? To learn something new, you have to be able to admit you don’t know everything. To learn from mistakes, you have to be willing to admit that you made a mistake.

And it’s not about listening to authorities. It’s about listening to evidence. That means when you read papers, don’t try to understand the conclusion- understand how they got to that conclusion- the evidence and the reasoning. And if the conclusion isn’t supported by the evidence, have a closer look at the evidence.

References

Dodson, P., Forster, C.A., Sampson, S.D., 2004. Ceratopsidae, in: Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., Osmolska, H. (Eds.), The Dinosauria, Second ed. University of California Press, Berkeley, pp. 494-513.

Longrich, Nicholas R. Titanoceratops ouranos, a giant horned dinosaur from the late Campanian of New Mexico. Cretaceous Research. 2011 Jun 1;32(3):264-76.

Lehman, T.M., 1998. A gigantic skull and skeleton of the horned dinosaur Pentaceratops sternbergi from New Mexico. Journal of Paleontology, pp.894-906.

Lehman, T.M., 1993. New data on the ceratopsian dinosaur Pentaceratops sternbergii Osborn from New Mexico. Journal of Paleontology 67, 279-288.

Longrich, N. R. 2010. Mojoceratops perifania, a new chasmosaurine ceratopsid from the Late Campanian of Western Canada. Journal of Paleontology 84:681-694.

Longrich, N.R., 2013. Judiceratops tigris, a new horned dinosaur from the middle Campanian Judith River Formation of Montana. Peabody Museum Bulletin 54, 51-65.

Osborn, H.F., 1923. A new genus of Ceratopsia from New Mexico, Pentaceratops sternbergii. American Museum Novitates 93, 3.