The Out-of-Africa Offensive

The Sapiens-Neanderthalensis wars lasted around 100,000 years from the first steps out of Africa until the last Neanderthals were killed.

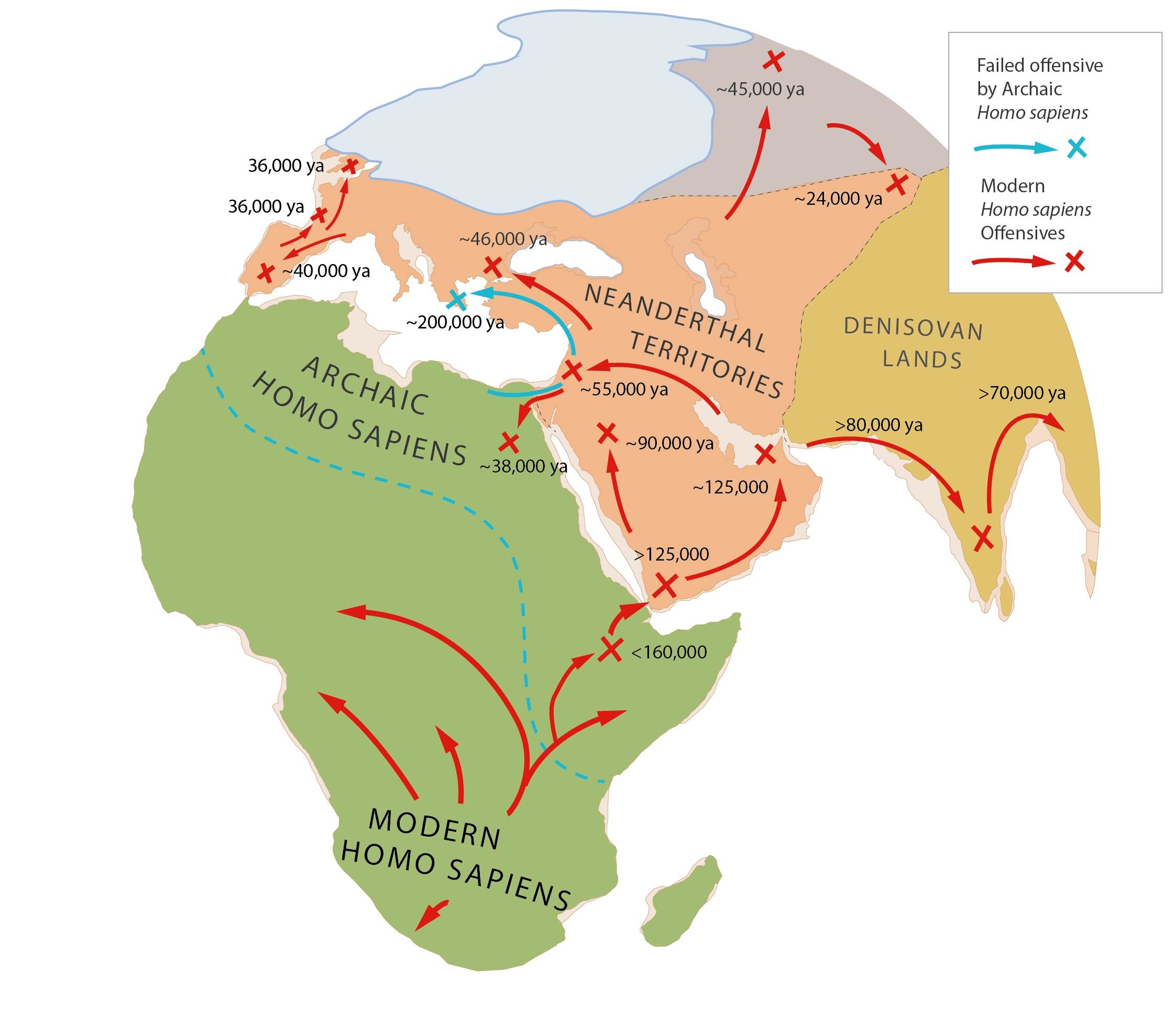

This map is my attempt to sketch out how it may have happened. It’s deliberately framed and drawn as a map of a military campaign, since (as I’ve explored in previous writings) it’s my contention that the replacement of Neanderthals by humans is very unlikely to have been peaceful, and instead was probably the result of tens of thousands of years of intensely violent tribal warfare, of the sort we see historically in hunter-gatherer cultures. Few behaviors are more intrinsic to humanity than warfare, and based on what we know of human cultures historically- both civilized and non-civilized- it defies belief to think that the meeting and replacement of one human culture by another occurred in a peaceful fashion. That’s just not how the human animal behaves- unfortunately.

This picture is necessarily very incomplete given that the archaeological record is very incomplete (this being a new area for me, my knowledge of it is also very incomplete, so there’s also that). There’s furthermore a lot of ambiguity in interpretation- just exactly what does it mean to call a skull “anatomically modern Homo sapiens” for example, and can we really tell when modern humans arrived where, based on stone flakes and points?

I have however tried to take a broad view- that is, to put together a picture that seems reasonable in light of what we know from skulls, and DNA, and stone tools, and traces of fire, and then considering each of these in light of these others, feeling more confident in inferences that are supported by multiple lines of evidence, and many data points.

For example, both artifacts and traces of fire suggest a very ancient occupation of Australia (65,000 ya and 70,000 ya) respectively. These observations tend to support each other- but also fit well with the idea of an early occupation of India (based on tools at 80,000 ya). And these observations in turn all these support a relatively early migration out of Africa (100,000 ya or earlier).

There’s a lot of guesswork- where is the border between Neanderthal lands and Denisovan lands- given that we have almost no Denisovan fossils? I’m guessing (since Indians have lots of Denisovan DNA) that India is Denisovan, whereas Neanderthals occupied the Middle East where modern people tend to just have Neanderthal DNA.

Did Neanderthals go into the Arabian Peninsula? Who knows. My understanding is that the tools are consistent with that idea, but early Homo sapiens had a similar toolkit, so it’s not impossible that these areas were inhabited by archaic Homo sapiens instead. It’s tentative- very much a work in progress, and doubtless will change a lot in years to come.

What emerges is a picture where, surprisingly, modern humans didn’t walk through the Sahara up the Nile and out of Africa via the Sinai- the most obvious route. Instead, tools suggest we crossed the Red Sea (much narrower since the icecaps locked up so much water in the Ice Age, lowering the sea levels), made our way up the Arabian Peninsula, and then shot along the coast. Although such a crossing could conceivably have been made without boats or rafts- many animals just swim between islands- this seems unlikely to me for the simple reason that a viable group of colonists, crossing even a very narrow Red Sea, would have included both men and women, and almost certainly young children and infants who could not themselves have swum.

The timings of the various occurrences outside Africa strongly support this scenario. There are tools assigned to Homo sapiens in India at 80,000 ya, and traces of human occupation in Australia at 65,000 years ago, and changes to fire regime there at 70,000 years ago, suggesting that’s when we actually arrived. Whereas it seems- remarkably- fully modern human beings didn’t arrive in Israel until far later, around 55,000 years ago.

Yes, there are Homo sapiens in Israel before then- the Skhul and Qazfeh people- but these don’t seem to be fully modern Homo sapiens, ancestors of modern Europeans and Asians; they had big brow ridges, and more primitive braincases, they weren’t the direct ancestors of Eurasian peoples like Socrates, Jesus, Gandhi, Jackie Chan, Jane Austen.

Fully modern people show up in Israel long after they reached India- or even Australia. How did they take so long to reach the Holy Land, yet rapidly reach southern Asia, Indonesia, and Australia?

The implication is that humans are using boats and/or rafts, and marine resources, possibly occupying uninhabited islands. This let them move rapidly along the coast. It’s probably not that traveling by boat was substantially faster- historically humans have covered vast distances on foot, and hunter-gatherers were highly mobile. Rather, it meant they met with limited resistance from Neanderthals or Denisovans, who as far as we know didn’t use boats. Facing a determined enemy, they could have used an island-hopping strategy to simply avoid conflict and find less well-defended beaches, bays, and islands.

In other words, the first people out of Africa may have been fishermen.

Once establishing a beachhead, they would have moved inland. That would explain how, in perhaps 10,000 or 20,000 years, humans got as far as Indonesia and into Australia, whereas it was a longer harder fight to move up into the Levant and then into Europe. The use of maritime technology, boats and fishing, would have enabled humans to avoid a head-on confrontation, at least initially- a flanking maneuver. This is, I concede, highly speculative.

What kind of weaponry they used is unclear. There’s suggestions that bows were around long ago, but descendants of early waves of migration- Australian Aborigines, the Clovis people in North America- lacked bows and instead had atlatls, which implies that the Out-of-Africa people (at least initially) used atlatls instead, and bows were exported later into North and South America, while failing to ever reach Australia.

A weapon these people almost certainly would have used is some kind of throwing stick- perhaps a boomerang. Neanderthals actually had crude throwing sticks. Boomerangs have a curious distribution today, occurring in Australia and historically in various other places like India and Egypt; then there’s a mammoth-ivory boomerang from Europe dating to 24,000 years ago. This suggests modern distributions of boomerangs are relict distributions, with these weapons being supplanted by other weapons- bows, slings, throwing clubs- over much of their formerly widespread range.

A curious pattern you see is that humans arrive in the Arctic, where Neanderthals didn’t live as far as we know, many thousands of years before they arrive in France, England, and Spain- or the farthest east parts of the Neanderthal lands, in the Altai Mountains. Again, that suggests our ancestors had to slowly fight their way through occupied lands, but could move more rapidly when avoiding a direct confrontation- using technology to exploit habitats Neanderthals didn’t. Presumably, humans had technology- fur clothing, warm shelters, firemaking technology- that allowed them to occupy cold regions Neanderthals couldn’t live in. They may then have expanded back down into Neanderthal lands- another flanking maneuver.

Perhaps the most striking aspect of this map is the timescale. From the horn of Africa to the Persian Gulf and then to England is a distance of around 9,000 kilometers, and it’s covered in ~90,000 years give or take a few tens of thousands. That suggests a very slow advance- 1 kilometer every 10 years, or 100 meters per year, or even less. That’s a football field (either American football or as we call it, soccer), a year.

Contrast this with the New World. Once humans got past the ice sheets into central and southern North America, they expanded all the way from Texas to Patagonia in maybe a little more than 1,000 years. Without other humans to contend with, humans were able to move rapidly, through plains, deserts, tropical rainforests to pampas- in around 30 generations.

The only plausible explanation I can see for why the Amerindians were able to rapidly expand through the Americas, whereas modern Homo sapiens took at least 50,000 years to reach western Europe and Central Asia, is that in Europe and Asia they faced determined resistance each step of the way.

Every inch of ground would have been fought over, facing determined resistance from Neanderthal tribes. Keep in mind that 100 meters a year is an average. Some years, it would have been more, perhaps if some climactic disruption caused Neanderthals to retreat, they might have moved tens or hundreds of kilometers. Other years, they may have fought for a few meters, barely held their own- or fallen back in the face of Neanderthal resistance. It wasn’t a blitzkrieg, but a long war of attrition, against an enemy we were fairly evenly matched against.

The pace of the offensive seems to have picked up over time. Our ancestors arrived in the Holy Land around 55,000 years ago. From there, it was about 10,000 years until they arrived in eastern Europe, then a mere 10,000 years more until they hit western Europe and Great Britain. Doubtless, humans had become far more sophisticated during this time- better weapons, better tactics, better tools, clothing, firemaking techniques, and so on. By the time they arrived in Western Europe, Homo sapiens’ advance seems to have been inevitable and unstoppable.

We also need to consider the political dimensions. Homo sapiens and Neanderthals could not have been unified political entities, we can’t think of the two species fighting one another like the Axis powers versus the Allies in WWII, or the NATO countries versus Warsaw Pact powers in the Cold War. Similar to the Plains Indians, Early Homo sapiens and Neanderthals likely lived in small bands, which in turn may have associated into tribes that shared languages, culture, and blood ties, but without strong central authority and hierarchy of the sort seen in agricultural kingdoms, city-states and nations. Tribes may in turn have allied with other tribes.

In this political system, sapiens would not necessarily have allied with other sapiens, any more than Napoleon sided with Russia, or Hitler with Stalin because they were both Homo sapiens. There would have been distinct tribes with distinct languages, cultures, belief systems, and depending on the circumstances, they would have been as likely to fight as ally with one another. The same is true, of course, for Neanderthals.

Neanderthals evolved over the course of around 300,000 years, about the same amount of time it took Homo sapiens to evolve, so it’s reasonable to suppose they were similarly diverse- different Neanderthal tribes may have been as linguistically and culturally distinct from one another as modern Maori, Tuareg, Bushmen, Ainu, and so on. And so everyone probably fought among one another, rather than presenting a united Neanderthal Nation versus a Sapiens Alliance.

The fundamental organizational units were the bands and tribes, not species, and so they would have fought- or allied- as bands and tribes. Human tribes probably fought other human tribes, and this almost certainly delayed their defeat of the Neanderthals. And Neanderthal tribes probably fought Neanderthal tribes, which would have prevented them from staging an effective resistance: they were not a unified entity.

It’s also worth considering the idea that Neanderthals and humans may have, on occasion, crossed species lines to form alliances with each other against common enemies.

This is what happens throughout human history. For example, when the Texas Rangers fought against the Comanche, they enlisted scouts from tribes hostile to the Comanche- as the ancient saying goes, “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” (this saying is ancient for a reason). Similarly, when colonizing the New World, the French and English each enlisted Indian tribes to help them fight each other. When European vessels showed up in the tiny island of Rarotonga in the South Pacific, an enterprising Polynesian chief, seeing an opportunity, wasted no time in enlisting the captain to turn the ships cannon’s against his rivals from another part of the island. The conquest of the Aztec empire by a small band of Spanish conquistadores was only made possible because a lot of the Aztec’s neighbors really, really didn’t like the Aztecs: the Aztecs were not defeated by the Spanish alone, but rather a Spanish-Indian alliance. It seems possible that Homo sapiens allied at times with Neanderthals to fight other Neanderthals- and other Homo sapiens. It is obviously difficult if not impossible to test this idea- but it would help explain one peculiarity of our species- the 2% or so Neanderthal DNA we have.

Looking back throughout history it’s also interesting the degree to which chance plays a role in determining the outcome of battles and the rivalry of empires. In a battle against Rome, the Greek general Pyrrhus suffers a major setback when an elephant matriarch panics after a young elephant in her herd is wounded. The behavior of this single elephant might have made the difference in this battle, and if it had gone better for Pyrrus, it may well have resulted in the Greeks triumphing over the upstart Romans and conquering them, rather than vice versa. If so, all of Western Civilization, and world history, would have played out very, very differently, for better or for worse.

Was the same true for ancient battles? We can imagine that a determined resistance against the first few people out of Africa, when they initially crossed the Red Sea, might have bought the Neanderthals more time. I suspect the cognitive gap between us and them was very narrow- Neanderthal tools are about as sophisticated as early Homo sapiens technology- and its possible that assuming they were less clever than us in some ways, in others, they were even more intelligent. For all we know, with a little more time, they and their culture might have evolved, might have become more sophisticated, and I’d be typing these words with massive Neanderthal fingers (more than ever appreciating my big, clunky Lenovo keyboard over the Mac ) and wondering why it was that the strange, gracile Homo sapiens from Africa went extinct when Neanderthals invaded Africa 100,000 years ago…

Once humans were safely established outside Africa, however, the outcome would not have been contingent on any single battle. Instead, a series of tribal conflicts- small-scale warfare, the result of an endless series of small raids, ambushes, and skirmishes between thousands of small bands, over years, centuries, millennia- would have determined the outcome. War between civilizations has a large degree of chance because everything rests on a few, very large battles. When everything rests on a few high-stakes poker games, luck plays a big role. But tribal battles involve many, small-scale events, so there’s less of a chance for good luck or bad luck to tip the tide; in the long run skill wins out. If Homo sapiens got unlucky in one skirmish, perhaps accidentally alerting their foes to their presence and losing the element of surprise- well there were a dozen more to be waged over the next few years, the loss of a few men wouldn’t make a massive difference in the long-term outcome.

That suggests to me that the ultimate triumph of Homo sapiens- whatever caused it- wasn’t pure, dumb luck. Homo sapiens kept winning against the Neanderthals, over and over. They weren’t just lucky, they were good.