Why did we replace the Neanderthals? The key might lie in our social lives

Why did humans take over the world while our closest relatives, the Neanderthals, went extinct?

It’s possible we were simply more intelligent, but there’s surprisingly little evidence that’s true.

Neanderthals seem to have been comparable to us in most ways. They had huge brains, language, and sophisticated tools. They made ,art and jewelry, and likely had spiritual beliefs. That raises a curious possibility— maybe the most important difference wasn’t between individual Neanderthals and individual humans, but in our social structures.

250,000 years ago, the Middle East, Europe and western Asia were Neanderthal lands, while Homo sapiens was restricted to southern Africa. 100,000 years ago, modern humans migrated into Eurasia. By 40,000 years ago, Neanderthals disappeared from Asia and Europe, and we’d replaced them. The slow but inevitable replacement of Neanderthals by Homo sapiens implies humans had an edge; but doesn’t tell us what it was.

Anthropologists once saw Neanderthals as dull-minded brutes lacking speech, or our sophisticated minds. If so, then maybe we just outwitted them. But we took a long time to displace them, which suggests our cognitive differences weren’t that large. And over and over, archaeological finds have shown that Neanderthals rivaled early humans in many ways. They had similar-sized brains, although distinct regions of the brain are enlarged.

The Acheulian hand-axes made by Neanderthals rival the sophistication and elegance of stone tools made by many modern hunter-gathererers

They also had refined tools and technology, like hand-axes and stone-tipped throwing spears. They may have mastered fire before modern humans did. They were deadly hunters, taking big game like mammoths and woolly rhinos, and also small animals like rabbits and birds. They gathered plants, seeds and shellfish. Hunting and foraging all those species demanded a deep understanding of animals, plants, and nature.

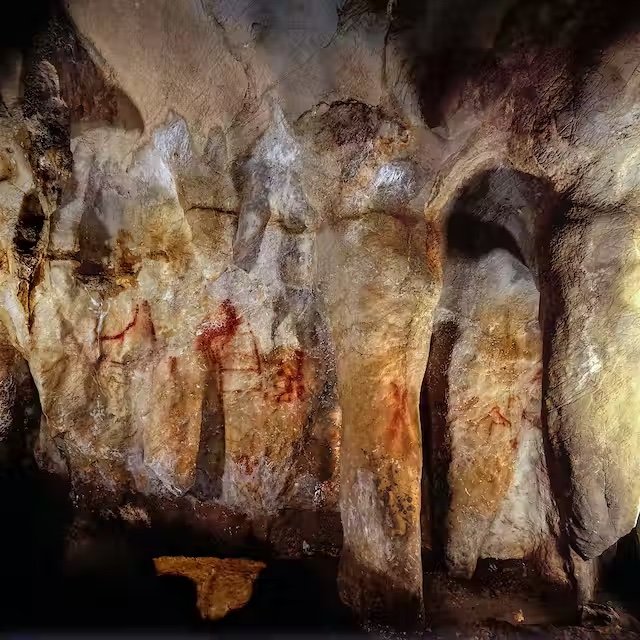

Neanderthals had a sense of beauty. They made beads, and created cave paintings. And they were a spiritual people. Neanderthals buried their dead with flowers; stone circles found inside caves appear to be Neanderthal shrines. Like modern hunter-gatherers, Neanderthal lives were probably steeped in superstition and magic; their skies full of gods, their nights haunted by ghosts, the caves inhabited by ancestor-spirits.

Neanderthal cave paintings

Then there’s the fact that we married them and raised children together; we couldn’t have been that different. But as intelligent as they were— we met them many times, over many millennia, and the result was always the same.

They disappeared. And we replaced them.

Why? To answer that question means understanding human societies. I’d argue it’s simply impossible to understand hominins as isolated individuals, any more than you can understand colonial animals like bees in isolation from their colonies. We’re social creatures; humans evolved to live in large, complex societies, not as individuals. We may have individual desires and motives, and move between social groups, but ultimately any individual’s survival is tied to larger social groups, like a bee’s fate is tied to its colony.

Modern hunter-gatherers probably provide our best guess at how early humans and Neanderthals lived. People like the Bushmen and Hadzabe gather families together to form nomadic bands of 10 to 60 people. These bands then combine into a loosely organised tribe of a thousand people or more. These tribes lacks a formal leader or political structures, but they’re loosely tied together by shared language and religion, marriages, family relationships, and friendships. Neanderthals societies may have been broadly similar, but with one crucial difference— their social groups were smaller than ours.

We know this because Neanderthals had lower genetic diversity than modern humans.

In a small group, genes are easily lost. If one person in ten carries a gene for curly hair, then in a band of ten, one person’s death can remove the gene from the population. In a band of fifty, five people would carry the gene, backup copies so to speak. Imagine genes as books, and each person as a library. The fewer libraries, the fewer the total number of book titles.

Recently, DNA was recovered from eleven Neanderthals living in a cave in the Altai Mountains of Siberia. Several individuals were related, including a father and a daughter; they were part of a single band. And these Neanderthals showed low genetic diversity.

Since everyone inherits two sets of chromosomes, one from their mother and one from their father, our DNA often has two versions of the same gene— for example, a gene for blue eyes from your mother and a gene for brown eyes from your father. But the Altai Neanderthals often had just a single version of each gene. That low diversity suggests they lived in small bands, averaging around 20 people.

It’s possible that the distinctive anatomy of Neanderthals favored small group sizes. Neanderthals were strong and muscular, and so they were heavier than Homo sapiens. So each Neanderthal needed more food, which meant a piece of land could support fewer Homo neanderthalensis than Homo sapiens.

Neanderthals might also have eaten more meat than modern humans. If so, that meant small bands, since the land would provide fewer calories to meat-eaters than people exploiting both meat and plant foods.

Having bigger groups gave humans a number of advantages.

Neanderthals, strong and handy with throwing spears were likely good fighters. Lightly built humans probably countered with bows, to attack from long range. But assuming Neanderthals and humans were equally dangerous in battle, humans would tend to win just due to their larger numbers. Being larger, their bands and tribes could both bring more fighters to a battle, and absorb more losses.

But setting aside advantages on the battlefield, big social groups have other, more subtle advantages over small social groups. Facing a band of 20 Neanderthals, a band of 30 humans brings more brains. More brains to solve problems, to engage in deception, to remember lore about hunting game and gathering plants, to remember techniques for crafting tools and sewing clothing. A bigger tribe also generates more ideas. And more people also mean more connections.

Network theory says a 20-person band has about 200 possible connections between its members, but a 30-person band can have over 400 connections; the potential connections in a network scale exponentially with group size. And information flows through along all these connections— news about the movement of people and animals, ideas for technology; myths, songs and language. Larger groups are qualitatively different than smaller groups; quantity has a quality all its own.

Consider ants. Individual ants aren’t exactly intelligent. But the interactions between individual ants lets colonies engage in complex behaviors. They make elaborate nests, they forage for food, they can hunt and kill animals many times an ant’s size. An ant is dumb, but the swarm behaves in an intelligent fashion. Likewise, groups of humans can solve complex problems an individual can’t- groups can design buildings, cars, and computer programs. They can fight wars, run companies and govern countries. Communities have an emergent intelligence vastly exceeding any member’s intelligence.

Humans aren’t unique in having big brains (whales and elephants have these) or in having huge social groups (zebras and wildebeest form huge herds). But we’re unique in combining these two things, which makes us very unusual.

To paraphrase John Dunne, no man — and no Neanderthal— is an island entire of itself; each is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.

We all form part of something larger. And throughout history, humans have gradually formed larger and larger social groups- bands, tribes, cities, nation-states, multinational alliances— to compete.

It may be our unparalleled ability to build large networks and communities of people that gave Homo sapiens the edge. Not only against nature, but against other human species.